The work of translating German colonial archives opens up a still largely under-explored field of research on the history of precolonial African art. By making descriptions, sketches, architectural plans, and photographs produced in the colonial period accessible in French and English, it becomes possible to reconstruct, at least in part, African visual worlds from before the conquest—their forms, materials, and ritual and political uses. These documents are of course, not neutral: they carry the gaze, biases, and symbolic violence of the colonial project. Yet it is precisely by reading them critically, and by confronting them with local knowledge, oral traditions, and contemporary African research, that they can become sources for a history of African art that emerges from the archives but is reinterpreted from the standpoint of Africa. My translation work is rooted in this perspective: shifting these documents from a colonial use toward a scholarly, educational, and memorial use that serves the concerned communities and today’s researchers. In this section, I present only a selection of these visual materials: images of sculptures, architectural surveys (such as plans of huts or palaces), photographs of ritual sites, everyday objects, and ornaments.

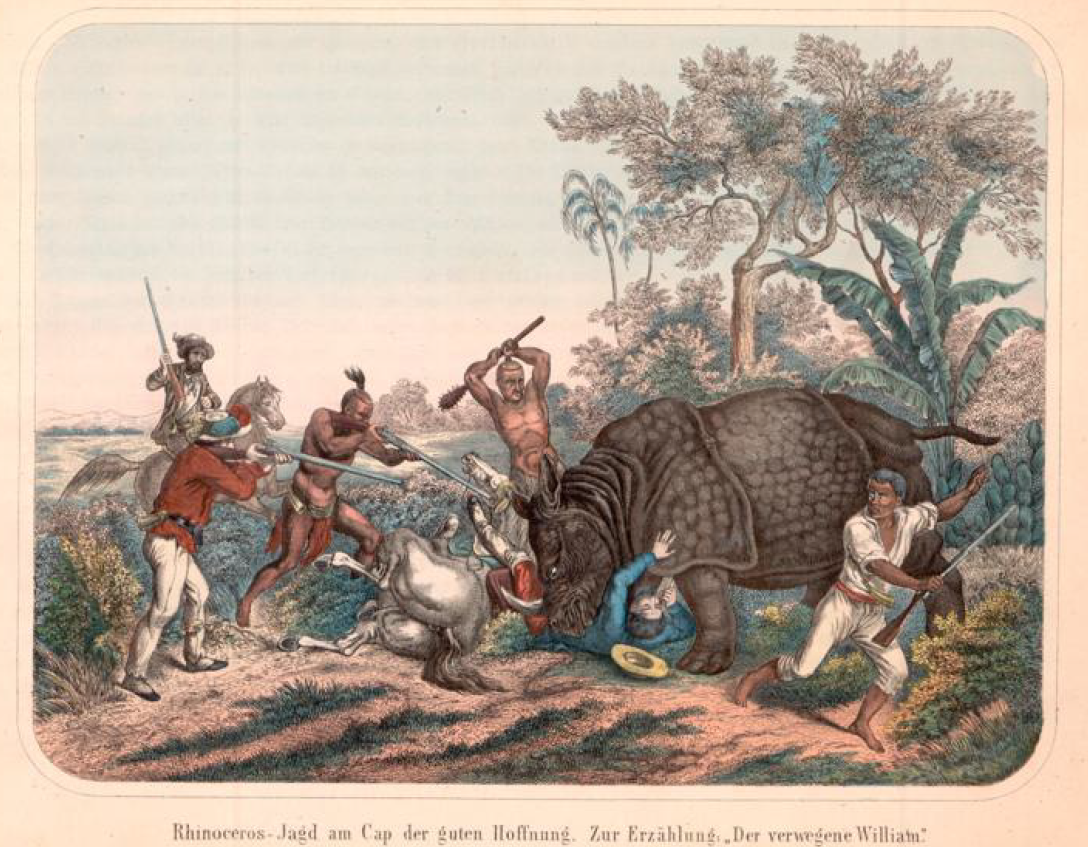

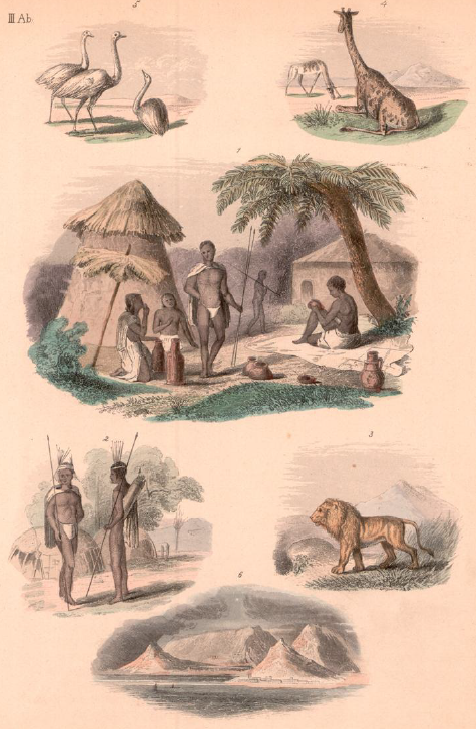

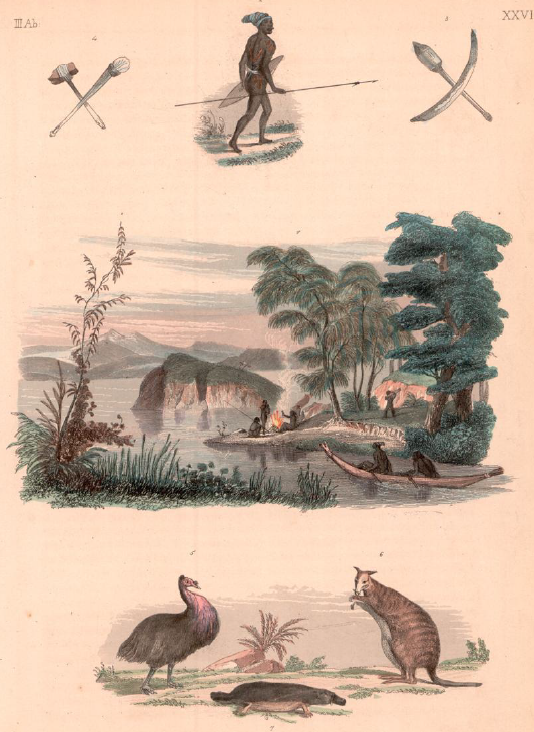

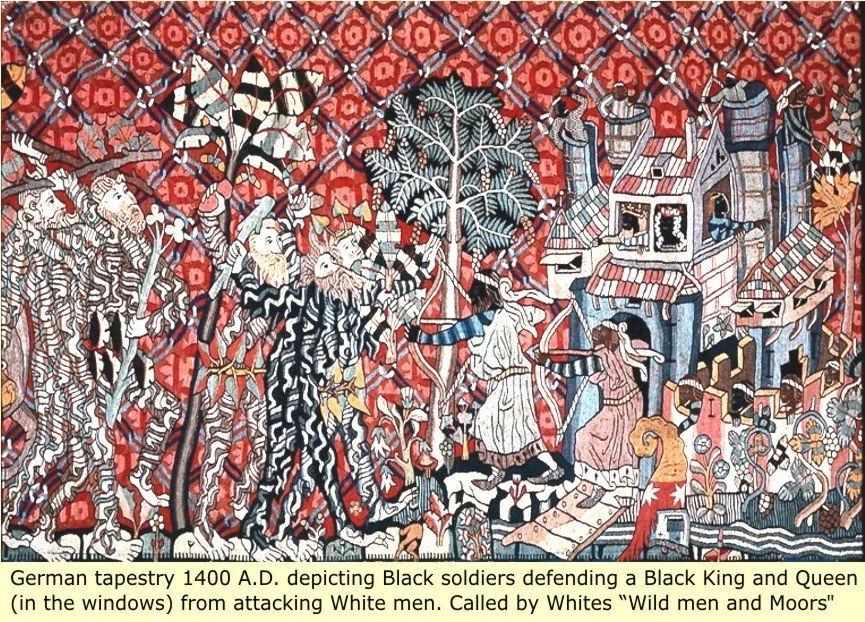

At the same time, this section does not present only what German archives recorded as African art — whether precolonial or colonial. It also presents German art representing Africa: illustrations, prints, paintings, title pages, didactic plates, and other visual productions that shaped how Africa was imagined, narrated, and consumed in Europe — more specifically within the German-speaking world from the eighteenth century through the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century. Tracing these images allows us to see which visual stereotypes, fantasies, and narrative templates circulated, how they were legitimized by “science,” travel writing, and exhibition culture, and how they helped to structure, over the long term, a Western gaze on Africa. These images are not meant to offer an exotic illustration of a “lost past,” but to serve as starting points for new investigations: reconstructing contexts of creation, identifying artists and workshops, understanding the political, religious, or social functions of these forms, and tracing the trajectories of objects now dispersed in Western museums and collections. In parallel, they invite a critical genealogy of representation—asking how Africa was pictured, for whom, and to what ends, and how these representational regimes interacted with collecting practices, museum taxonomies, and the histories of objects themselves.

The aim of this section is therefore twofold:

1. To reinvigorate research on precolonial African art by making visual and textual materials available that have long been difficult to access;

2. To offer a space for critical reflection on how these images were produced, archived, captioned, circulated, and sometimes distorted—both in colonial documentation and in German visual culture—in order to better reinsert them into African histories of art, memory, and heritage, while also clarifying the visual construction of “Africa” within European modernity.

Recontextualized and accompanied by rigorous translations, these images are meant to support the work of researchers, students, artists, and curators, but also to enable African and diasporic audiences to reclaim fragments of their visual history—long confiscated by colonial languages and institutions—and to critically examine the European images that helped define Africa in the Western imagination.

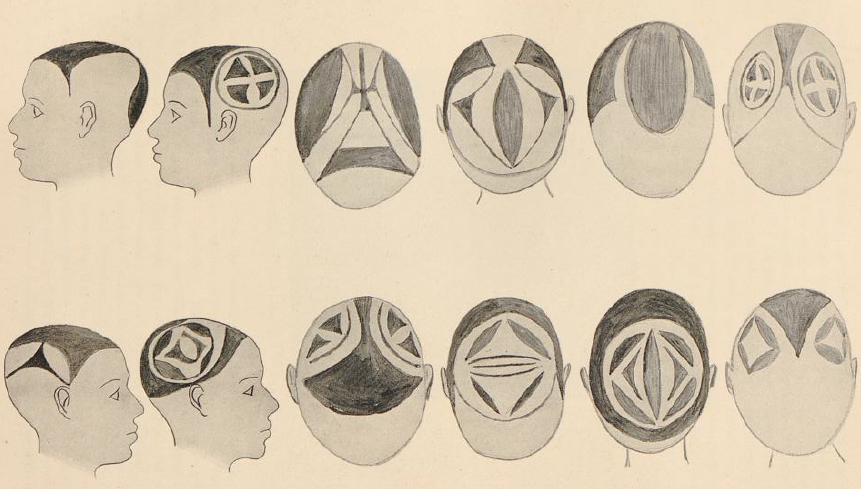

Hairstyles in Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908, p. 57.

Photograph after original paintings by the woman Orok (lizards, leopard, dog), in Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 145.

10. Sun and moon, 11. Halved calabash 12. Chameleon 13. Cocoa pod 14. Wild boar 15. Goat 16. Dog 17. Chicken In Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 122.

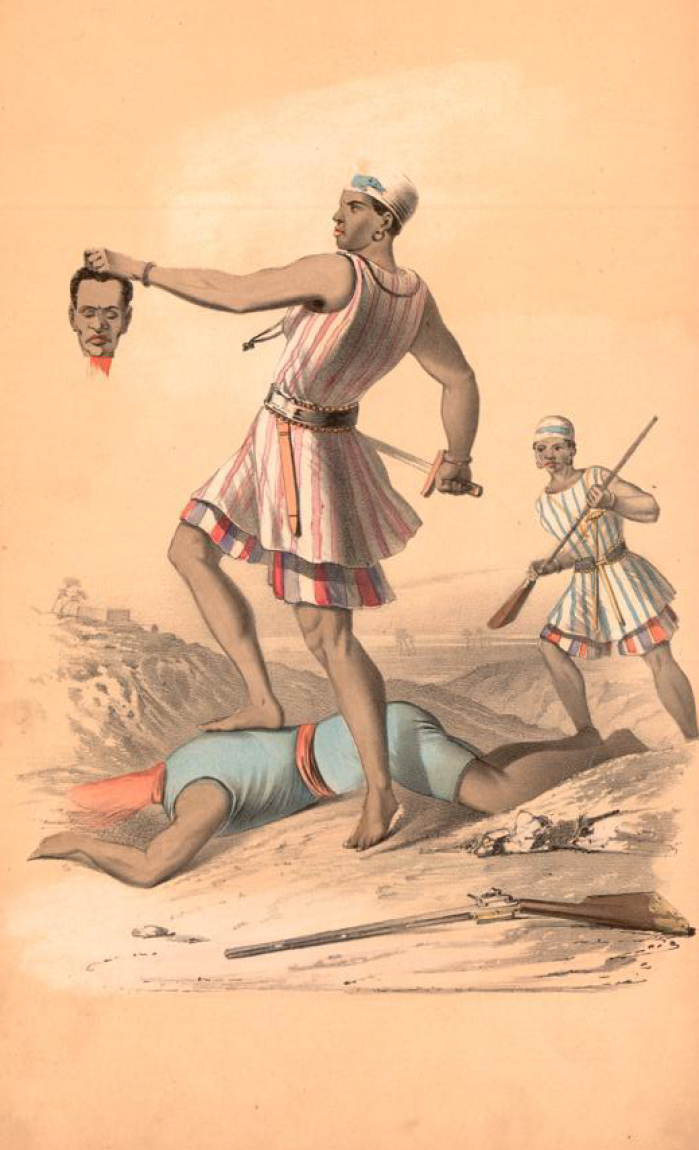

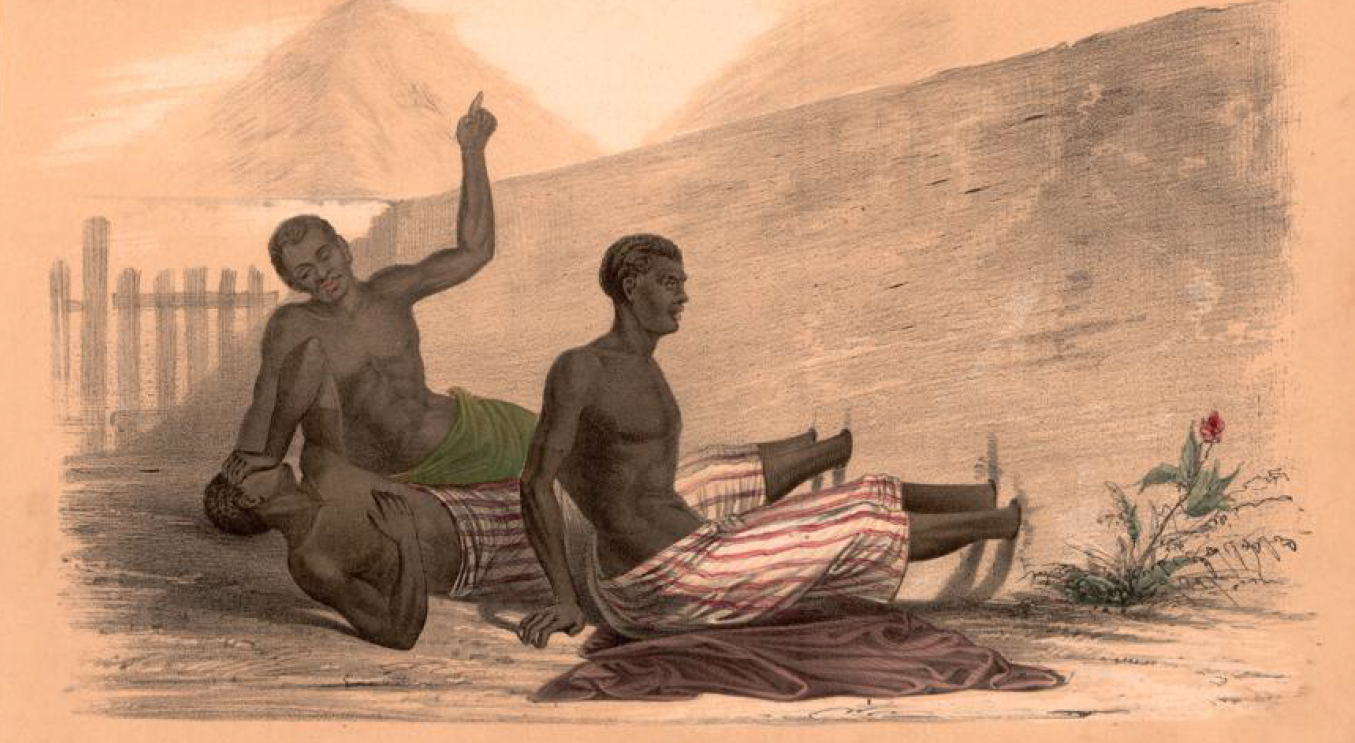

Female soldier of King Ghezo’s guard (Dahomey) holding up a severed head. Source: Joseph Josenhans, Bilder aus der Missionswelt für die deutsche Jugend, 1855.

1. Lizard. 2. Man with whip. 3. Plant. 4. Fish. 5. Butterflies. 6. Flying squirrel. 7. Crocodile. 8. Snake. 9. Ngbe-juju. In Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 130.

Plaiting patterns on mat bags in Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908, p. 111.

Fig. 67. Boki chicken house (round shape). Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 85.

Obaschi. Domestic chapel in Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908, p. 3.

The architecture of a hut among the Kiziba (a tribe living in East Africa near Lake Victoria Nyanza). House construction: a, the finished house; b, the house framework in its initial stages; prevailing wind direction. Source : Hermann Rehse, Kiziba: Land und Leute Eine Monographie, 1910, p.9.

Nkang, dance mask of the Cross River natives. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p.5.

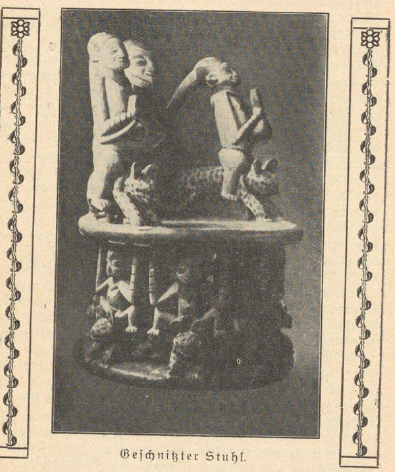

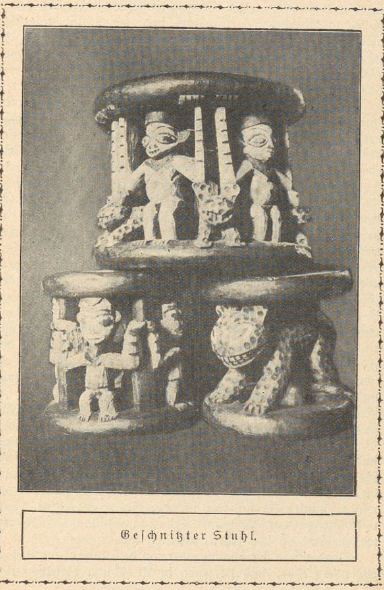

Fig. 22. Typical armchair in Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908, p. 3. Fig. 20. Ground plan of a hut. I, II. Open interior space. a. Depression. c. Earthen bench. e. Earthen plinth. g. Doorway. III. Chamber. b. Hearth. d. Sleeping places. f. Passage. Fig. 21. Hearth. a–b. Seating bench. c. Calabashes or clay jars with fresh water. d. Calabashes, with wooden ornamentation in front. e. Fireplace. f. Drying rack. g and h. Storage place for calabashes. Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 38.

Autumn fashions from Cameroon, in Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908, p. 71.

Fig. 93. Plaiting pattern on a large mat bag. Fig. 94. Plaiting pattern. In Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908, p. 112.

Fig. 101 a and b. String figure game (“cradle” game). a “Suspension bridge”. In Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908.

The interior of a well-built suspension bridge. In Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908, p. 122.

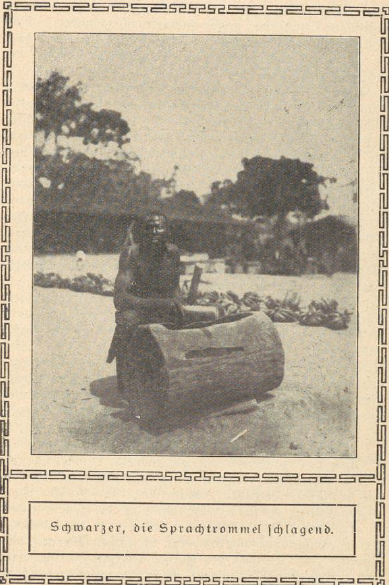

The large wooden drum used for dance music in Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908, p. 137.

Haussa Dance, Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokulmente, 1908, p. 145.

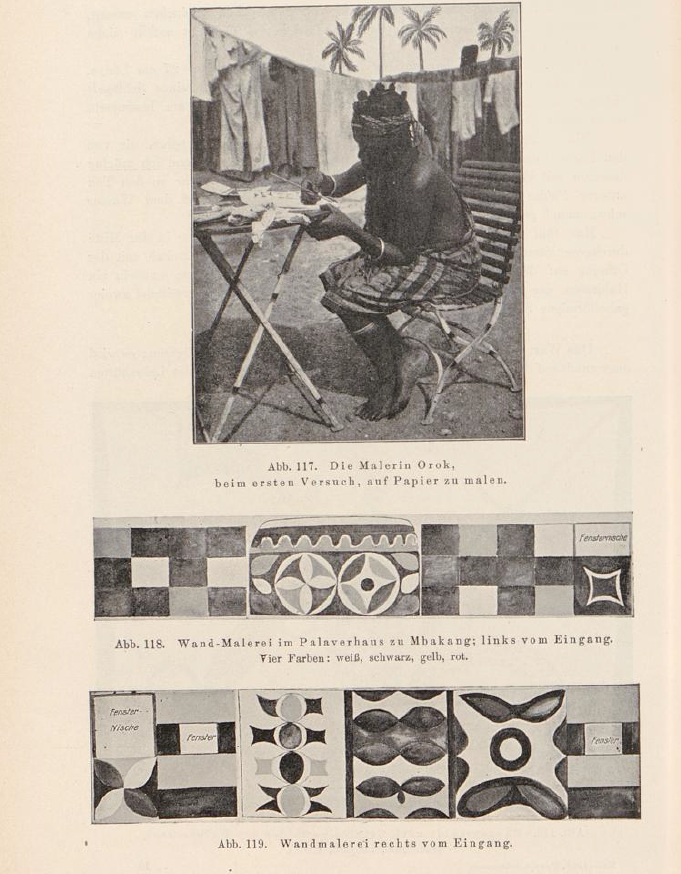

Fig. 117. The painter Orok, in her first attempt at painting on paper. Fig. 118. Wall painting in the palaver house at Bakang, to the left of the entrance. Four colours: white, black, yellow, red. Fig. 119. Wall painting to the right of the entrance, in Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 146.

Fig. 120. After original paintings: man smoking a pipe on the left, woman on the right. Fig. 121. After an original painting; the numbers indicate the order in which the six figures were painted. In Ekoiland, Cameroon. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 147.

Fig. 122. Wall painting on the exterior wall of a house in Ekoiland. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 148.

Fig. 123. A famous wall painting in Ekoiland: palaver house in Okuri, “the Ngbe-juju”. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 149.

Typical masks of the Cross River people. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 155.

Typical masks of the Cross River people. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 154.

Knives and knife handles. In Ekoiland, Cameroon, Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 157.

Fig. 132. Carved wooden combs (pyrography/woodburning work). Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 149.

Signs for the numbers from 1 to 20. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 209.

A dance mask. Source: Alfred Mansfeld, Urwald-Dokumente, 1908, p. 213.

Fig. 30. Hairstyles. a. kihara, worn by girls b. nkogato, worn by boys and unmarried young women c. kuezi, worn by small children d. bishuren-yonza, worn by small children Source : Hermann Rehse, Kiziba: Land und Leute: Eine Monographie, 1910, p.28.

Fig. 44. Daua horn. Fig. 45. Sultan’s daua horn. Fig. 46. Chopping knife. Fig. 47. Muyo arm knife. Fig. 48. Walking stick. Source : Hermann Rehse, Kiziba: Land und Leute: Eine Monographie, 1910, p.36.

Fig. 75. Board game among the Kiziba. Source : Hermann Rehse, Kiziba: Land und Leute: Eine Monographie, 1910, p.36.

Fig. 77. A Kiziba wooden mask of the court jester. Source : Hermann Rehse, Kiziba: Land und Leute: Eine Monographie, 1910, p.64.

3. War song 4. Ode to women) Source : Hermann Rehse, Kiziba: Land und Leute: Eine Monographie, 1910, p.72.

German officer, Captain Kund. Source: Curt von Morgen, Durch Kamerun von Süd nach Nord: Reisen und Forschungen im Hinkerlande 1889 bis 1891 ., 1893, p.25.

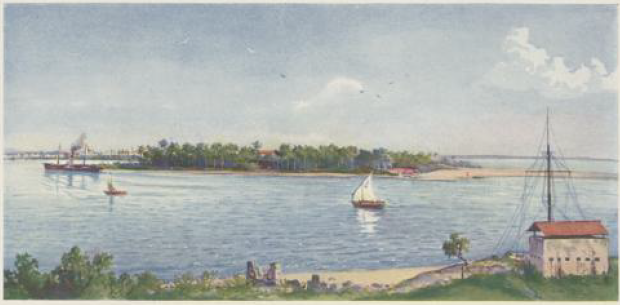

Harbor entrance of Dar es Salaam, the capital of German East Africa. Watercolour by R. Duschek. Source: H. Fonck, Die Naturschönheit deutscher Tropen: die Bevölkerung und Erschliessung, 1911.

Martin Paul Samba, in Curt von Morgen, Durch Kamerun von Süd nach Nord: Durch Kamerun von Süd nach Nord: Reisen und Forschungen im Hinkerlande 1889 bis 1891 ., 1893, p.31.

A Yaoundé woman playing music for the dance. Curt von Morgen, Durch Kamerun von Süd nach Nord: Durch Kamerun von Süd nach Nord: Reisen und Forschungen im Hinkerlande 1889 bis 1891, 1893, p.40.

An elephant hunt in Cameroun Curt von Morgen, Durch Kamerun von Süd nach Nord: TDurch Kamerun von Süd nach Nord: Reisen und Forschungen im Hinkerlande 1889 bis 1891 ., 1893, p.65.

War games at King Nguila’s court. Cameroon, Curt von Morgen, Durch Kamerun von Süd nach Nord: Durch Kamerun von Süd nach Nord: Reisen und Forschungen im Hinkerlande 1889 bis 1891 ., 1893, p.86.

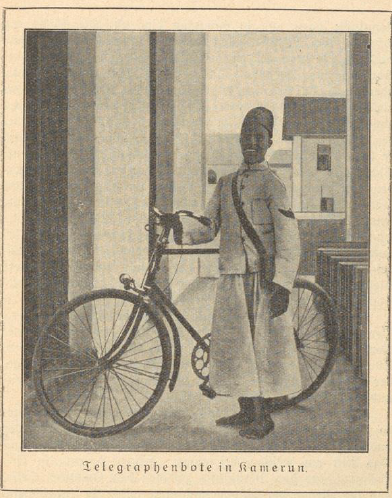

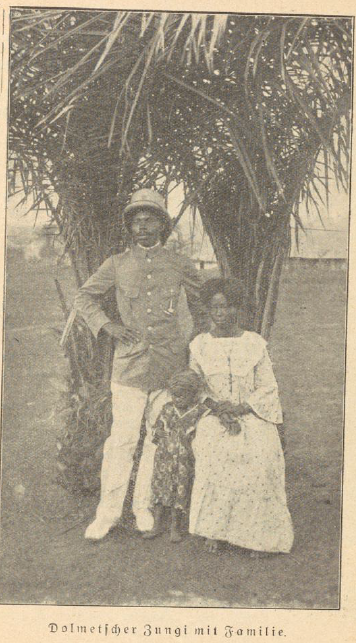

Lieutenant Dominik and his attendants, 1894. Cook Aman Sudani (Sudanese); King Ioory (Kru boy); Soldier Sennessi (Sierra Leone). Source: Hans Dominik, Kamerun: Sechs Kriegs - und Friedensjahre in deutschen Tropen, 1901, p.12

Group of the police force in Cameroon dating from 1894. 1. Sergeant Krause 2. Gunsmith Zimmermann 3. Lieutenant Dominik 4. Hospital orderly Seebe 5. Police Sergeant Biernatzki Source: Hans Dominik, Kamerun: Sechs Kriegs - und Friedensjahre in deutschen Tropen, 1901, p.13

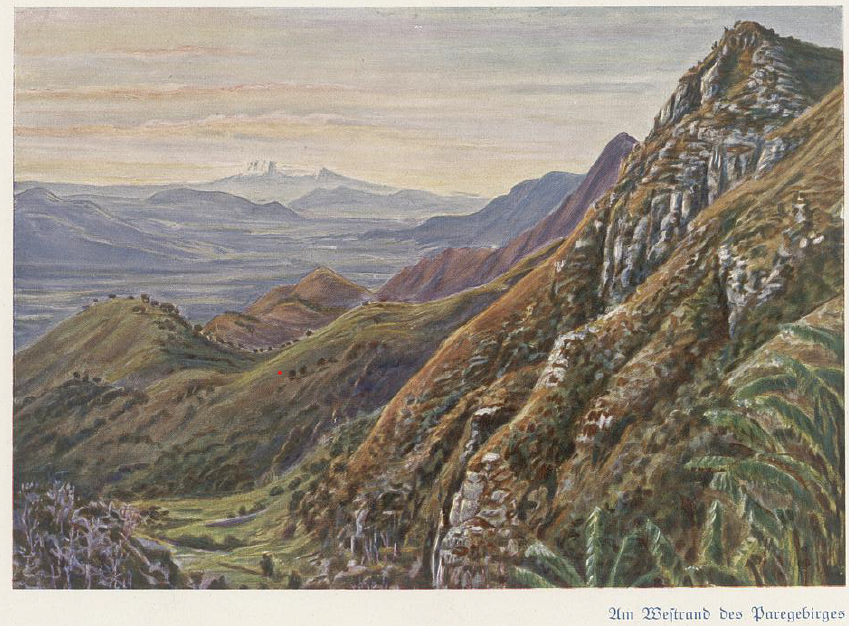

At the western edge of the Parege Mountains. (located in northeastern Tanzania, in the Kilimanjaro Region) Source : J.J. von Dannholz, Im Banne des Geisterglaubens: Züge des animistischen Heidentums bei den Wasu in Deutsch-Ostafrika, 1916.

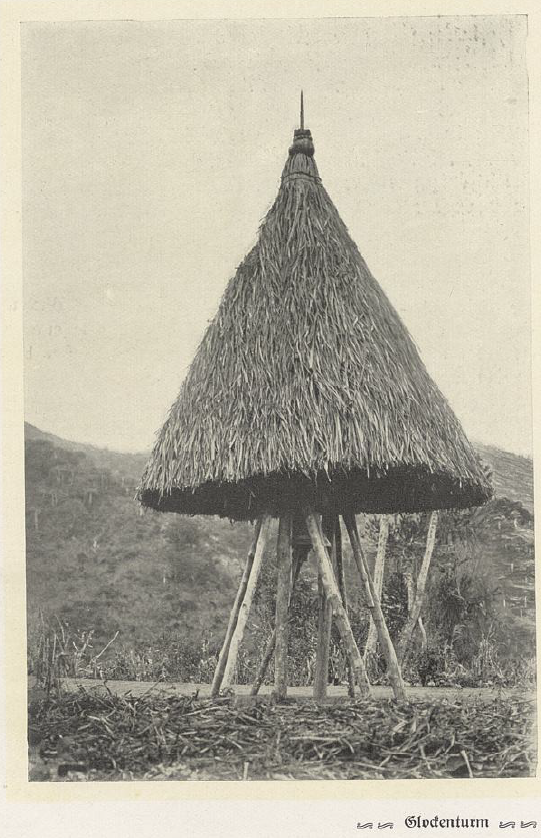

A bell tower, Source : J.J. von Dannholz, Im Banne des Geisterglaubens: Züge des animistischen Heidentums bei den Wasu in Deutsch-Ostafrika, 1916, p.129.

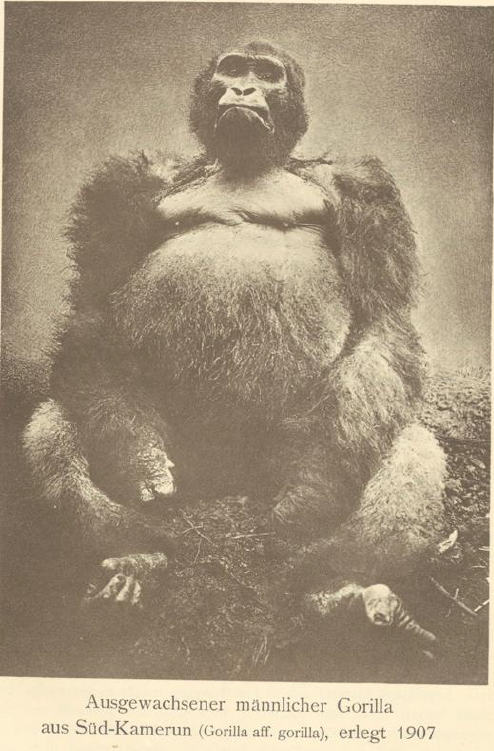

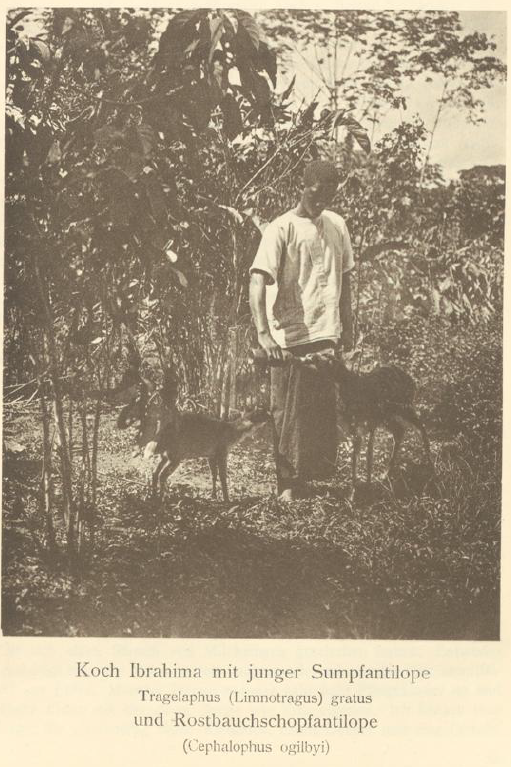

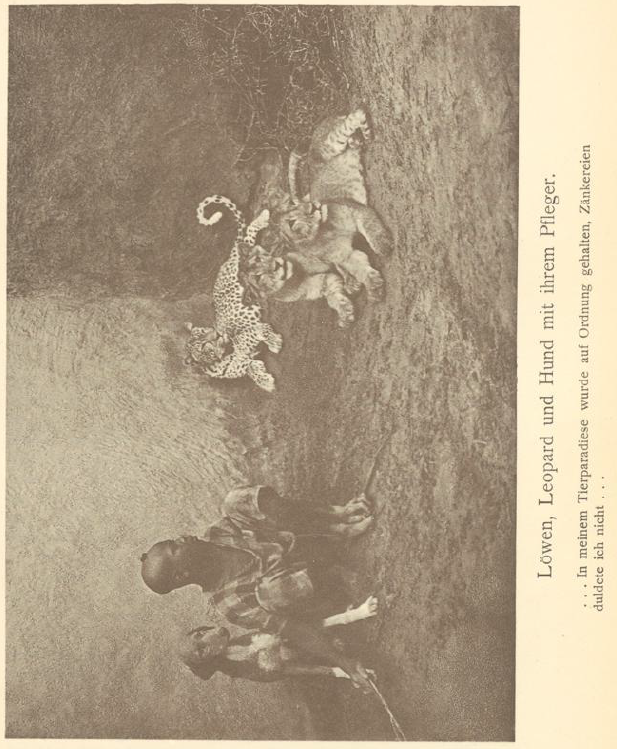

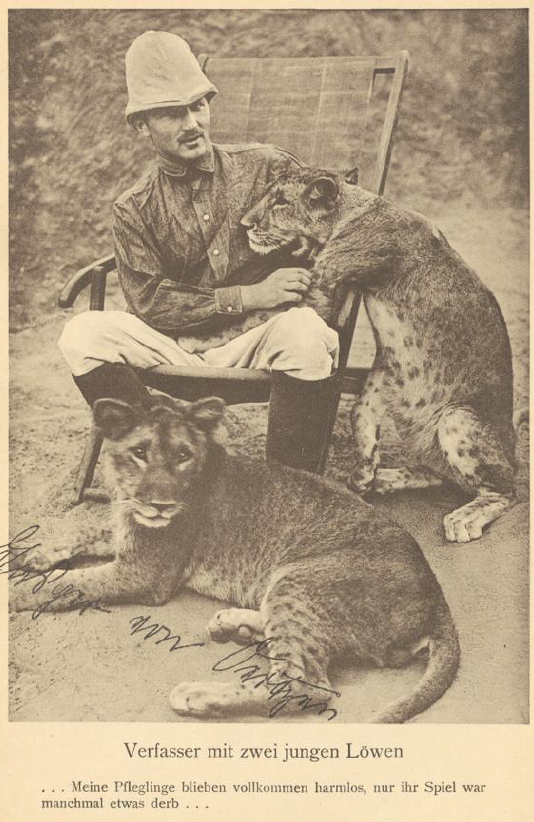

Fully grown male gorilla from southern Cameroon, killed in 1907. Source: Jasper von Oertzen, In Wildnis und Gefangenschaft: Kameruner Tierstudie, 1913, p.5.

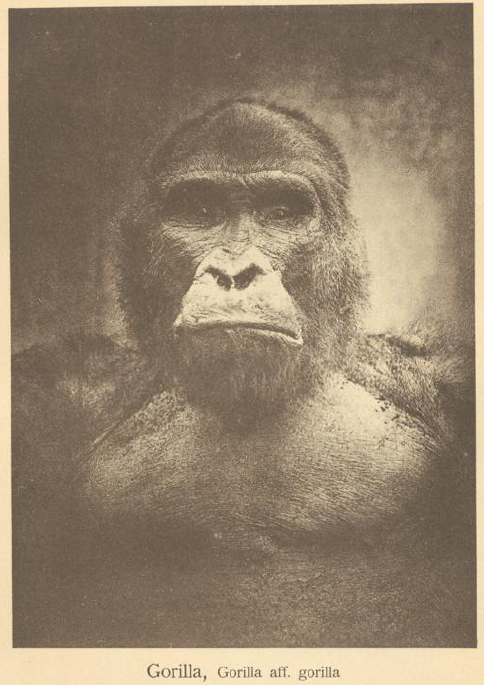

A gorilla. Source: Jasper von Oertzen, In Wildnis und Gefangenschaft: Kameruner Tierstudie, 1913, p.8.

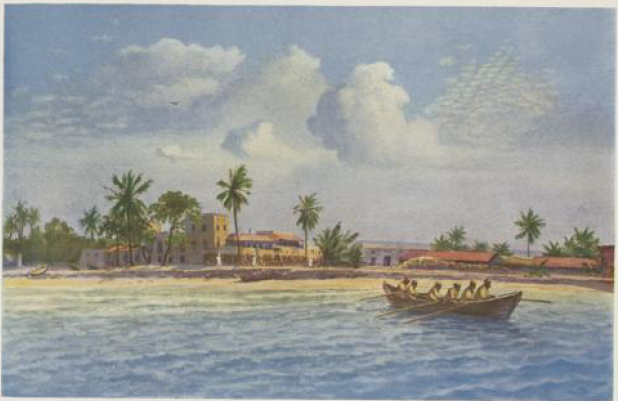

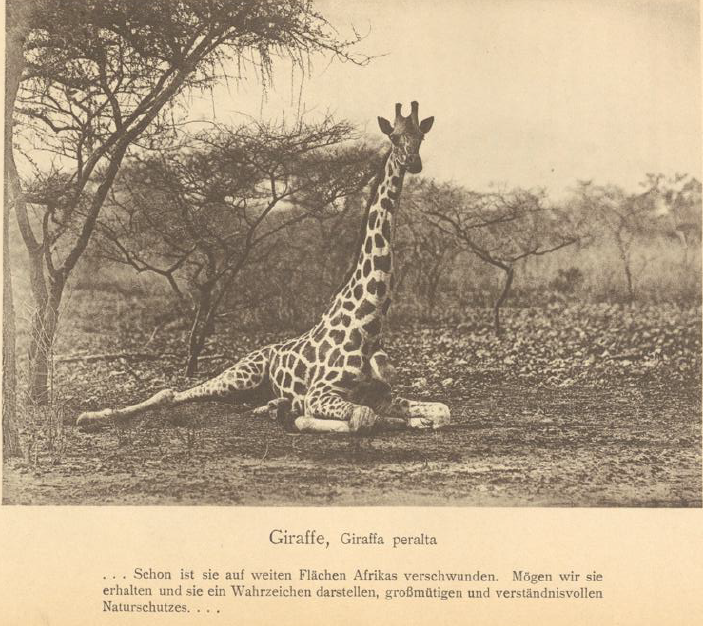

Kilwa Kiwindje (a historic town on Tanzania's coast known for its mix of Swahili and German colonial architecture and its history as a hub for the 19th-century slave trade). Watercolour by R. Duschek. Source: H. Fonck, Die Naturschönheit deutscher Tropen: die Bevölkerung und Erschliessung, 1911.

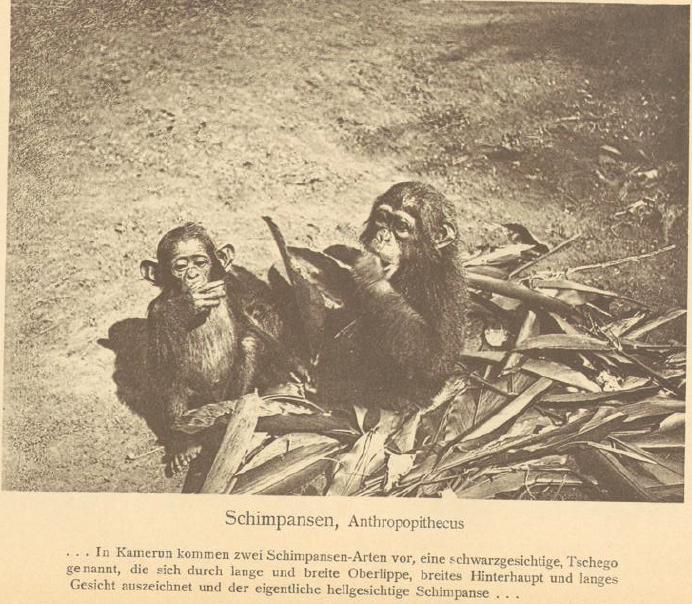

Chimpanzees in Cameroon. Source: Jasper von Oertzen, In Wildnis und Gefangenschaft: Kameruner Tierstudie, 1913.

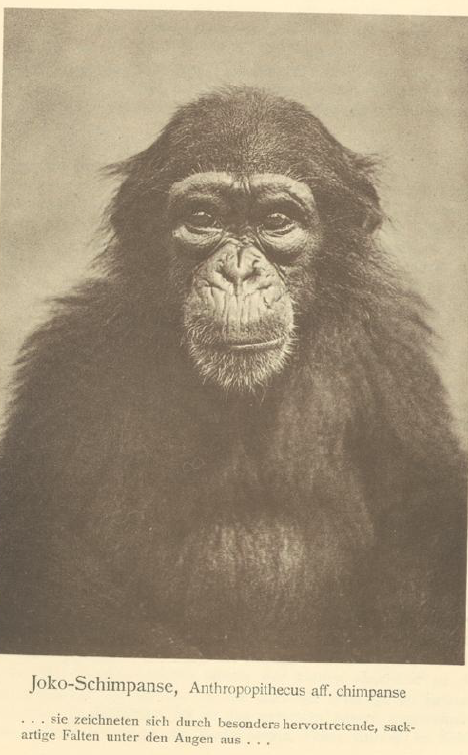

A chimpanzee from Jokon, in Cameroon. Source: Jasper von Oertzen, In Wildnis und Gefangenschaft: Kameruner Tierstudie, 1913.

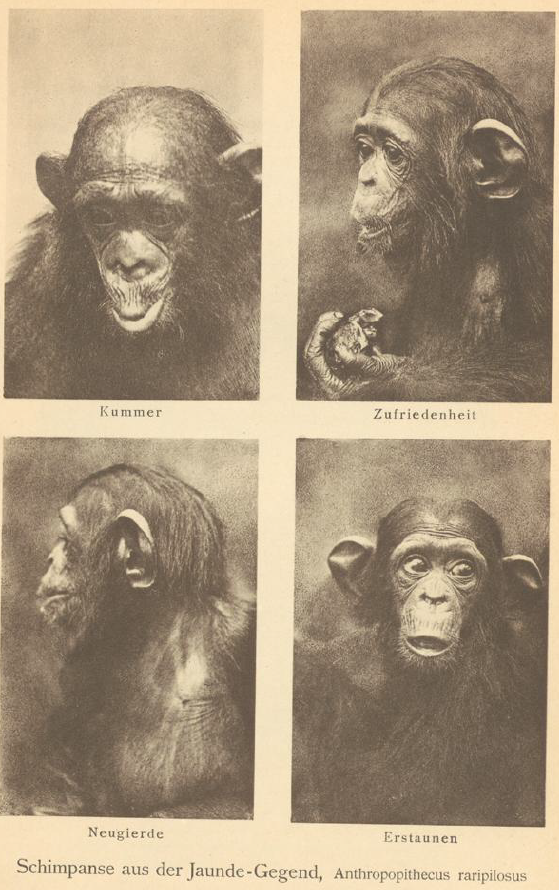

Emotions expressed by chimpanzees: (top left) grief, then (top right) contentment, (bottom left) curiosity, and finally (bottom right) astonishment. Chimpanzee from the Yaoundé area, Anthropithecus raripilosus. All great apes have expressive facial expressions. Source: Jasper von Oertzen, In Wildnis und Gefangenschaft: Kameruner Tierstudie, 1913.

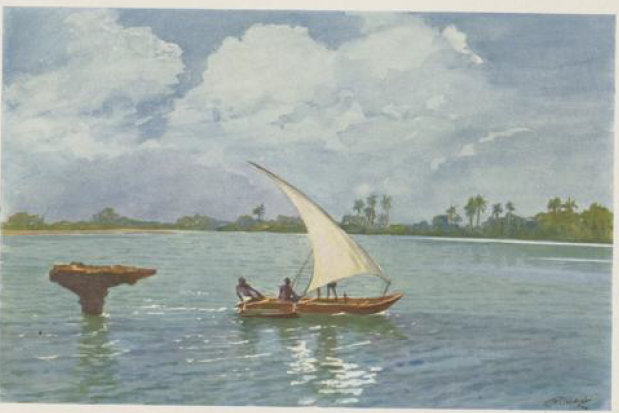

A small fishing craft of local fishermen off the coast of Dar es Salaam. Watercolour by R. Duschek. Source: H. Fonck, Die Naturschönheit deutscher Tropen: die Bevölkerung und Erschliessung, 1911.

Stanley in Zanzibar, Source: Stanley's Reise durch den dunklen Welttheil, 1880.

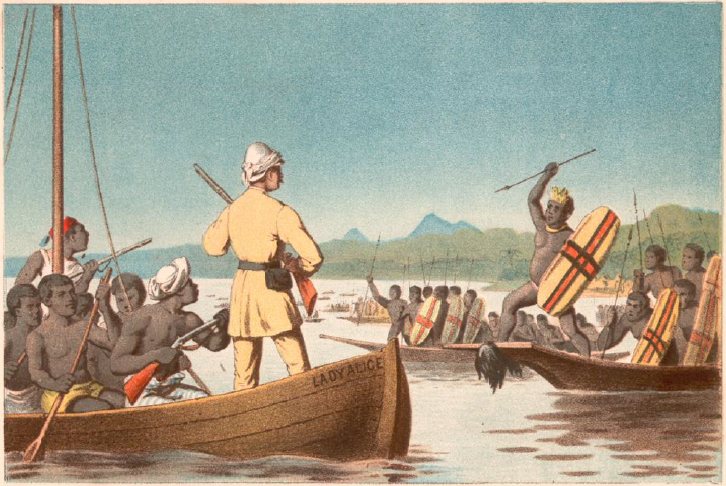

Armed encounter on the river: Stanley and the Wangwana in a canoe with rifles, facing other African canoes armed with spears. Source: Stanley's Reise durch den dunklen Welttheil, 1880.

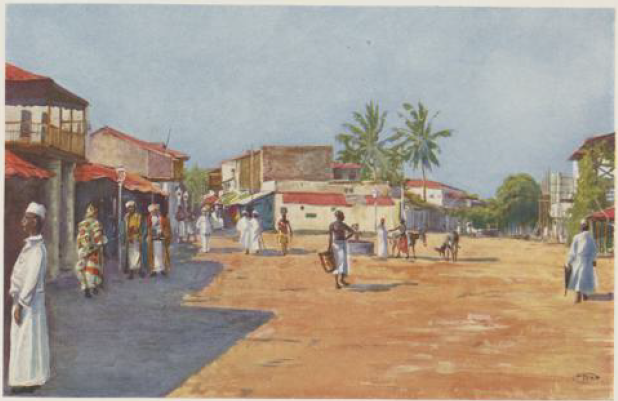

Merchants’ Street in Dar es Salaam. Watercolour by R. Duschek. Source: H. Fonck, Die Naturschönheit deutscher Tropen: die Bevölkerung und Erschliessung, 1911.

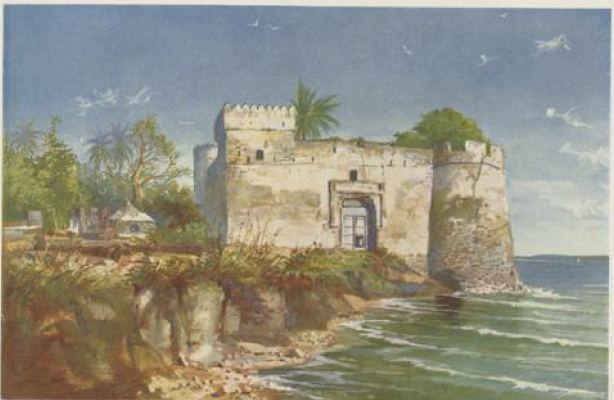

An Arab-style fortress on the island of Kilwa Kisiwani in Tanzania. Watercolour by R. Duschek. Source: H. Fonck, Die Naturschönheit deutscher Tropen: die Bevölkerung und Erschliessung, 1911.

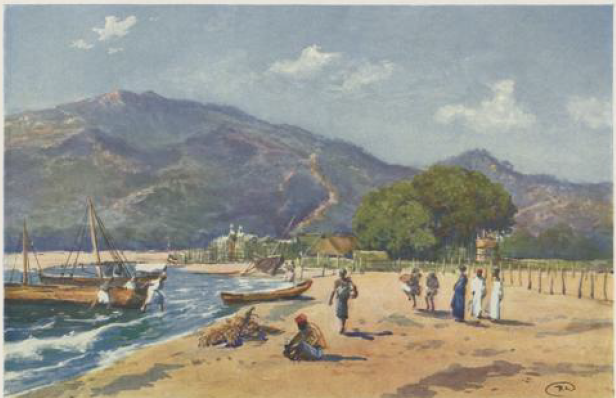

Alt-Langenburg Station on the northern shore of Lake Nyassa in Tanzania. Watercolour by R. Duschek. Source: H. Fonck, Die Naturschönheit deutscher Tropen: die Bevölkerung und Erschliessung, 1911.

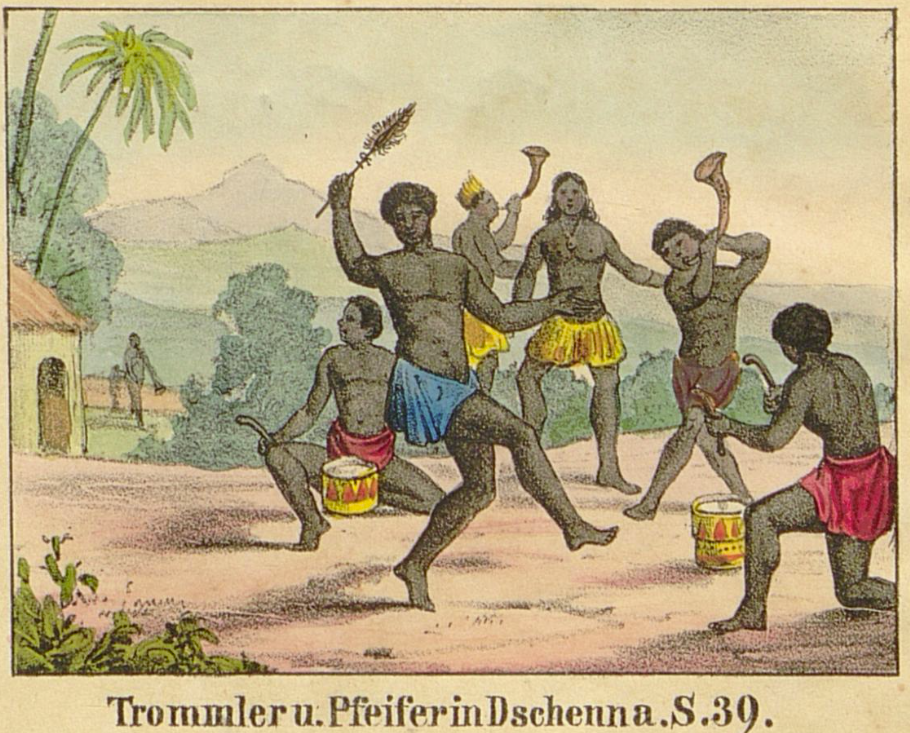

Drummers and fife players in Djenné. Source: Richard Landers & John Landers, Die Entdeckung des Nigers in Afrika : Eine unterhaltende und belehrende Reisebeschreibung für die Jugend. 1843.

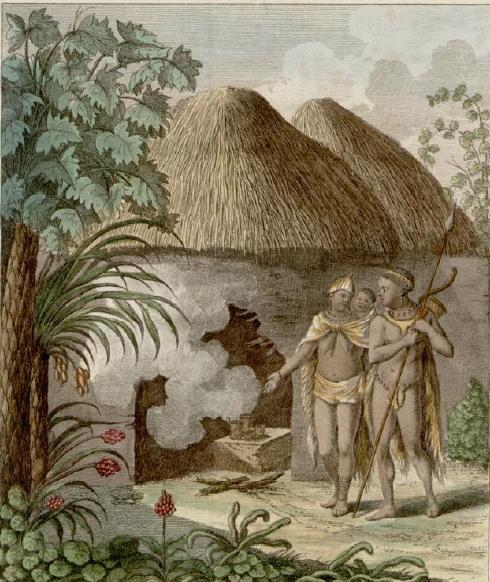

A fetish-maker. Source: Richard Landers & John Landers, Die Entdeckung des Nigers in Afrika : Eine unterhaltende und belehrende Reisebeschreibung für die Jugend. 1843.

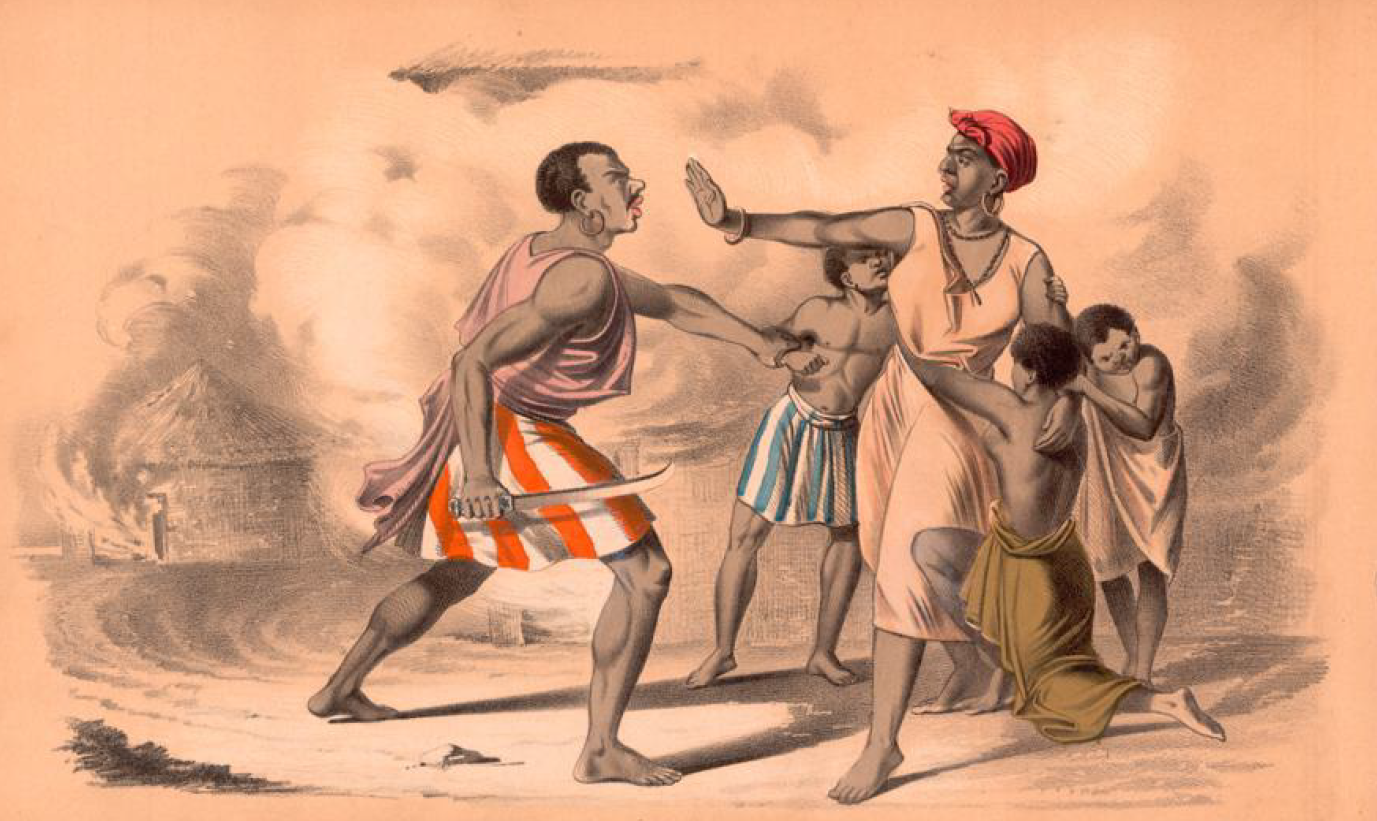

Slave-raiding scene in Africa: a mother tries to shield her children during an attack as one child is seized to be taken into slavery. Source: Joseph Josenhans, Bilder aus der Missionswelt für die deutsche Jugend, 1855.

Abeokuta (Egba country, east of Dahomey): persecution of newly converted Christians—arrest and punishment of the captives. Source: Joseph Josenhans, Bilder aus der Missionswelt für die deutsche Jugend, 1855.

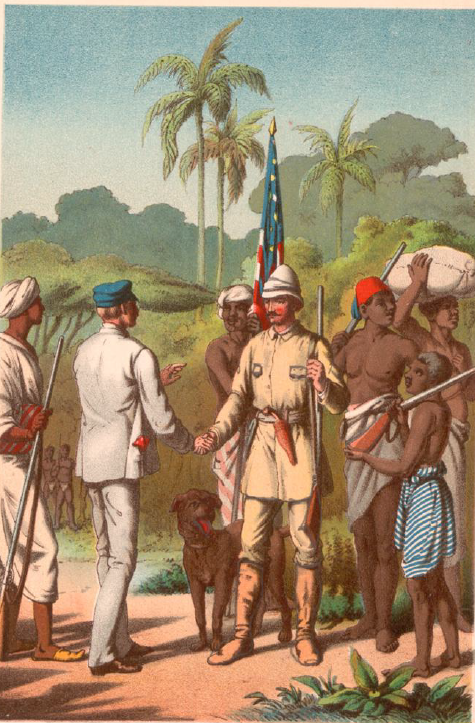

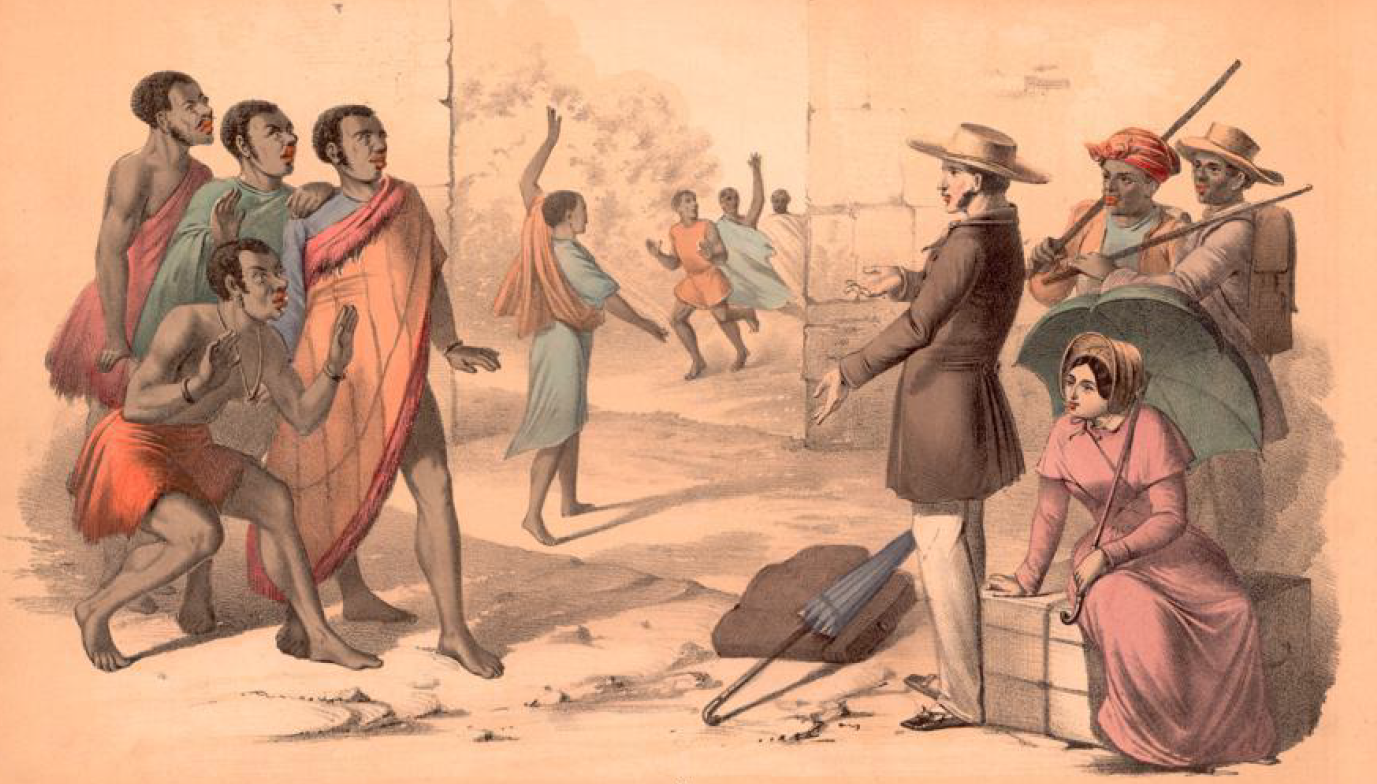

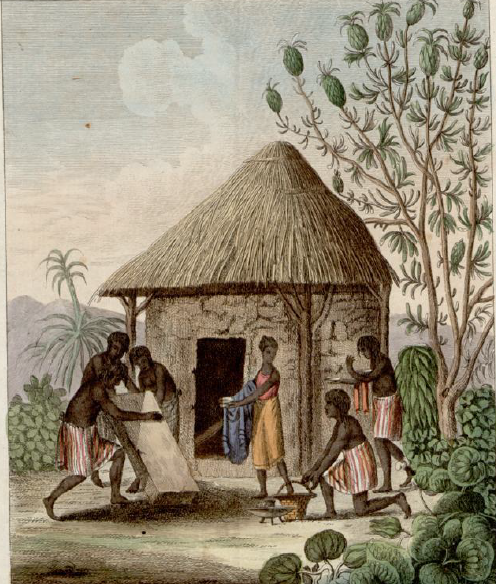

The first visit of a missionary to a Black African town in the interior of Africa. Source: Joseph Josenhans, Bilder aus der Missionswelt für die deutsche Jugend, 1855.

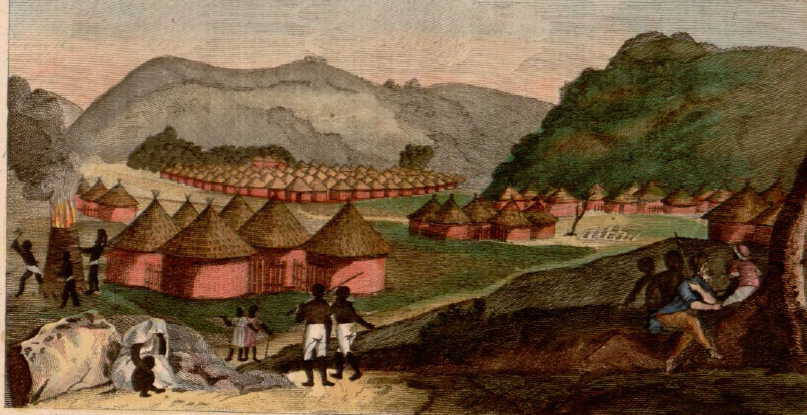

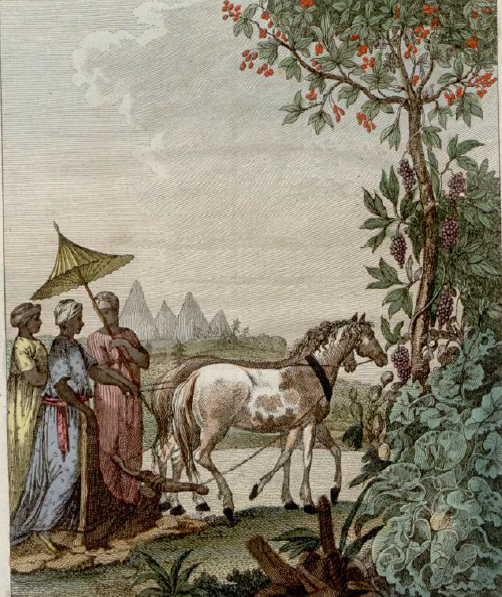

View of the town of Kamalia. Source: M. chr. Schulz, Mungo Park's Reise in Afrika, 1805.

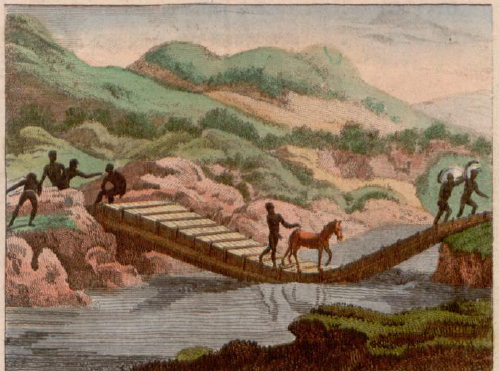

The suspension bridge over the Baffin River (or Black River). Source: M. chr. Schulz, Mungo Park's Reise in Afrika, 1805.

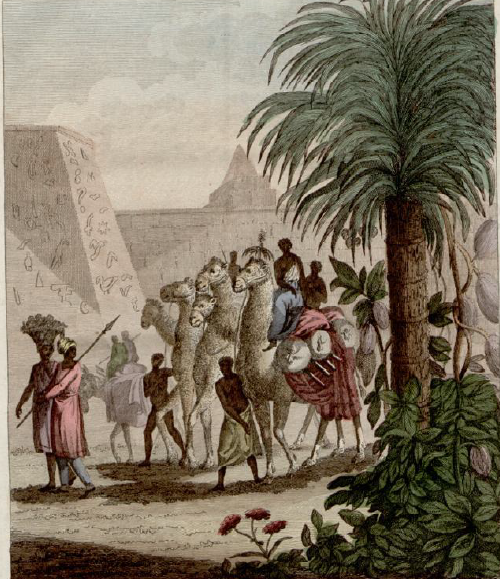

Ali in his tent at the camp near Benown. Source: M. chr. Schulz, Mungo Park's Reise in Afrika, 1805.

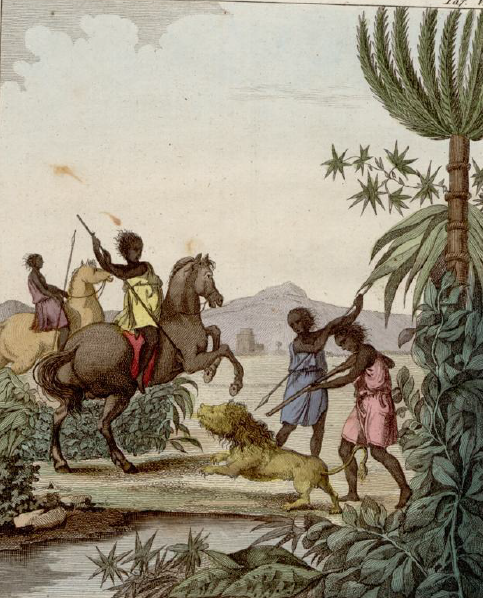

The mounted bodyguard of the Sheikh of Bornu. Source: Karl Friedrich Voltrath Hoffmann, Die Völker der Erde, ihr Leben, ihre Sitten und Gebräuche, zur Belehrung und Unterhaltung, 1840.

African warriors in the service of the Sheikh of Bornu. Source: Karl Friedrich Voltrath Hoffmann, Die Völker der Erde, ihr Leben, ihre Sitten und Gebräuche, zur Belehrung und Unterhaltung, 1840.

In der Tierbude (In the menagerie), by Paul Friedrich Meyerheim, Berlin, 1894

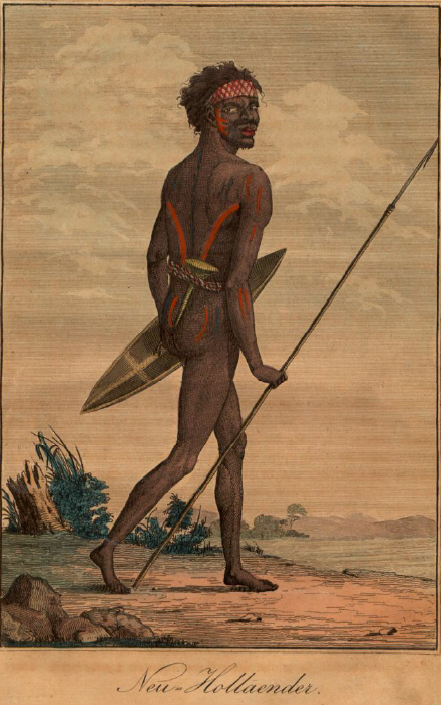

A New Hollander. Source: Karl Friedrich Voltrath Hoffmann, Die Völker der Erde, ihr Leben, ihre Sitten und Gebräuche, zur Belehrung und Unterhaltung, 1840.

Princess-Abbess Franziska Christine of Palatinate-Sulzbach with the court “Moor” Ignatius Fortuna, painting by J. Schmitz, c. 1770. (Princess Franziska Christine Foundation, Essen).

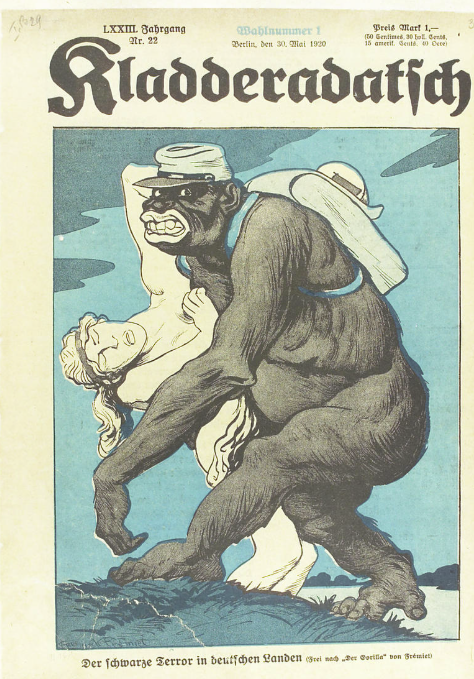

A satirical Kladderadatsch cartoon (Berlin, 30 May 1920) depicts a gorilla abducting an unconscious white woman, under the racist headline “Der schwarze Terror in deutschen Landen” (“Black terror in German lands”). Unknown artist, Kladderadatsch 73/22, p. 317; digitized copy held by the Heidelberg University Library.

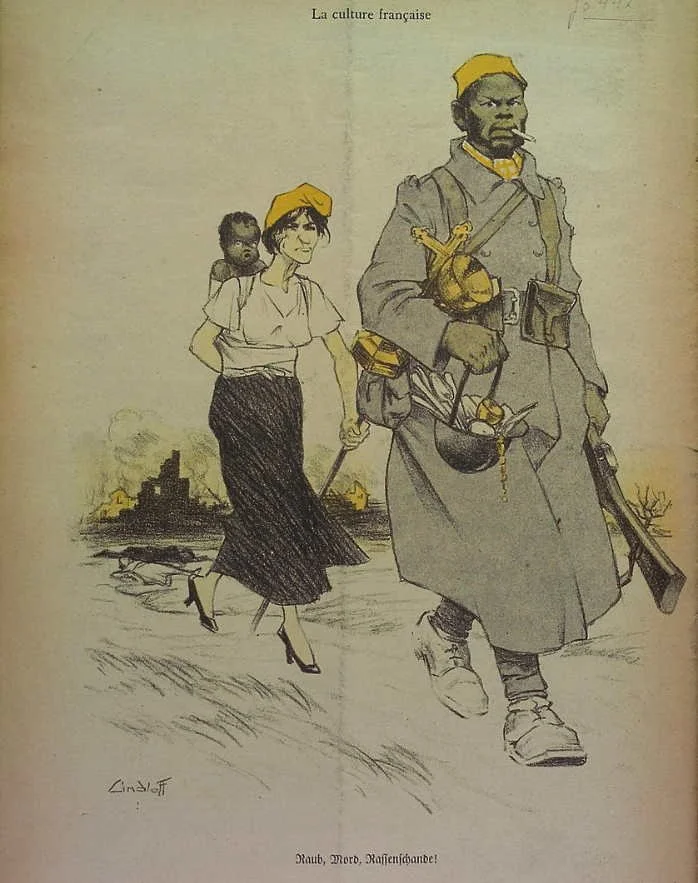

“French Culture.” The cartoon depicts a French colonial soldier shown as having attacked and violated a French woman; the caption below reads: “Robbery, murder, and racial defilement.” Source: Kladderadatsch, no. 25 (1940), Heidelberg collection.

Somali Dance by Max Pechstein, 1910